Enzymes in action

That enzymatic activity requires a precise balance between flexibility and stability is a widely accepted concept. However, key questions remain: How do motions on different timescales relate to each other and contribute to this balance? Have proteins evolved so that substates necessary for activity are preferably accessible?

We have developed approaches that allow quantitative and residue-specific measurements of dynamics in enzymes during catalysis by NMR spectroscopy. Strikingly, we found for several enzymes that the rate-limiting step for the overall turnover is a conformational change and not the chemical step. In other words, nature has “perfectionized” the enzyme to lower the energy barrier for chemistry, but collective motions are the price to be paid.

Moreover, we recently showed that motions in enzymes are not random but preferentially follow the pathways that create the configuration capable of proficient chemistry. This situation is analogous to protein folding, which is biased to sample only a small portion of the energy landscape. The expansion of the concept of nonrandom sampling of conformational space for efficient biological function—from folding to conformational rearrangements within the folded space—combines both phenomena through the energy landscape.

We are also investigating the hierarchy in space and time for protein dynamics. By comparing a mesophilic and hyperthermophilic enzyme pair, we identified a linkage between three different “tiers” of dynamic timescales: (1) thermally driven, fast (picosecond), local atomic fluctuations; (2) faster (nanosecond) motions of whole segments; and (3) larger amplitude, collective, slower motions (microsecond to millisecond), the timescale of catalysis. Importantly, we were able to demonstrate that those dynamic features are directly connected to function.

We propose that the pre-sampling of conformational states needed for catalysis and selective binding of substrates to these substates might be a general paradigm of enzyme catalysis. We are attacking the next immediate questions: How does a protein move from one energy valley into another, and what are the pathways and the transition states? Can minor conformational substates be predicted from known structures? Can we apply the knowledge gained about physical principles of proteins to design proteins with desired functions? Can we successfully incorporate a dynamic view into rational drug design?

The two substrate molecules in green are “hidden” in the active site in the closed state where phosphoryl-transfer happens. The visualized opening is the rate-limiting step for this kinase.

Evolution of Enzymatic Power and Complex Signaling

Our success in characterizing energy landscapes of enzymes and our first steps toward understanding the molecular pathways of conformational transitions have prompted us to begin applying these lessons to the development of artificial enzymes. While these first designer enzymes are a breakthrough, their catalytic turnover rates have been very low, most likely because we do not yet understand the defined and efficient changes in structure during catalysis. To address this principal question, we recapitulate a proven successful “design” of enzymes, the work of natural evolution. While the calculation of phylogenetic trees has become very popular (and meaningful) in the last years due to the huge explosion of sequences of diverse organisms, many basic questions of molecular evolution are unresolved, such as (1) Were the ancestors promiscuous enzymes from which specificity evolved? (2) Would it therefore be easier to design desired function from ancestors? Almost completely missing in the evolutionary field is the detailed biophysical characterization of ancestors and the lineage from those to our modern enzymes. Our first resurrected enzymes (up to ~3 billion years back) are not only active, but indeed give clues about the evolution of protein dynamics as an essential part of catalysis.

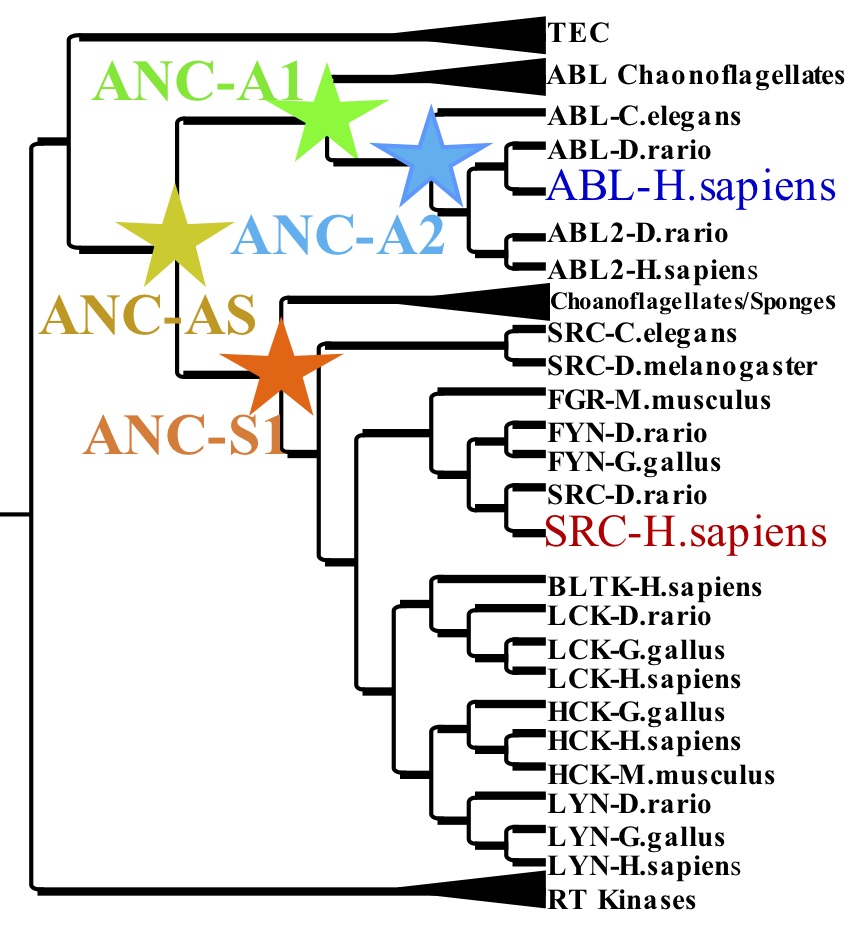

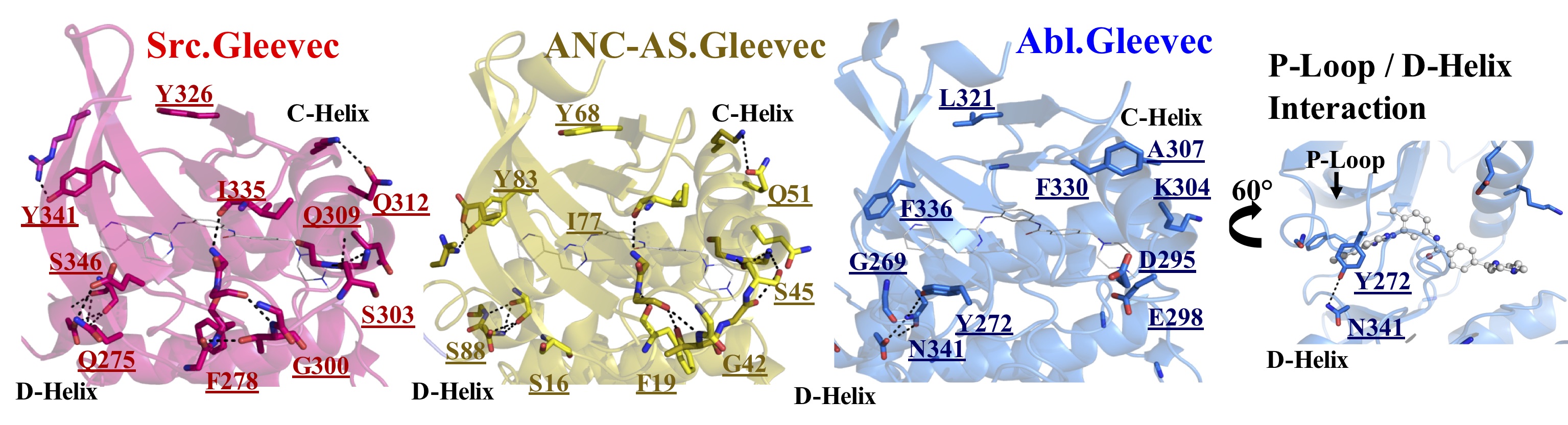

The Evolution on modern tyrosine protein kinases Abl and Src via ancestral resurrection

X-Ray structures of 1.5 Billion year old ancestor (ANC-AS) reveal molecular mechanism of Gleevec selectivity for cancer kinase Bcr-Abl. Loss of H-bonds remote from the Gleevec binding site result in increased protein dynamics needed to allow for P-loop kinking to “hug” the drug (right).

Molecular Mechanism of Phosphorylation-Mediated Signaling

Phosphorylation is a widely used mechanism in signaling. Through a combination of NMR structural and dynamic experiments, we found that signaling does not work through a mec hanism like a light switch (on, off) but rather through a population-shift mechanism; the active state is already populated to a low percentage before phosphorylation, and phosphorylation shifts this preexisting equilibrium. In other words, this sampling of substates is essential for phosphorylation, shifting the textbook paradigm of phosphorylation inducing a new structure. We are exploring the energy landscape for this signaling protein, including both the inactive/active interconversion and the folding. One key question in biology is how proteins can quickly change among distinct structures (needed for function) without unfolding. We anticipate that lessons learned for this kinase are widely applicable to other kinases.

Mechanism of Signaling Mediated by Prolyl Isomerization

Prolyl isomerases, the enzymes that catalyze the reversible cis/trans isomerization of prolyl peptide bonds, have been implicated to play a crucial role in many biological processes, including cell cycle control, ion channel conductance, cell signaling, neurodegeneration, cancer, transcription, and HIV virulence. However, the molecular mechanisms by which these enzymes affect such a variety of biological processes are poorly understood. We have used NMR spectroscopy together with in vivo experiments to shed light into the molecular mechanism of how these enzymes, which do not break or make bonds but just accelerate a 180° rotation about the peptide bond, control cell cycle, cocaine addiction via metatropic glutamate receptor, chemotropic nerve guidance, and tubulin dynamics through the Alzheimer’s protein tau. Catalysis of the natively folded protein substrates, such as the HIV capsid, the Trp channel, the synaptic receptor mGluR, and tau are indeed the trigger for the found phenotypes. In a search for new inhibitors, we are characterizing the energy landscapes for human CypA and human Pin1, two of the most important prolyl isomerases.